Editor’s note: The following article by Carola Splettstoesser was previously published in One Earth Magazine Issue No. 21, Spring 1996.

A spectacular, huge blue and white striped tent, the size and shape of the Universal Hall occupies the entire village green, leaving only a small area to display peculiarly-shaped eco-friendly modes of transport—bicycles. Are we ‘back to nature’, on the camping site again (the Findhorn Foundation Community having begun, as we all know, in a small caravan, growing cabbages and later people)? Has it all now, in October 1995, come full circle with a huge canvas marquee at its centre?

Yes and no. Yes, because there was a lot of talk about the need to reduce consumerism and live sustainably at a more human scale. Yes, because during this seven day Eco-village Conference 350 people from over 40 countries came to re-create the Earth, presenting and envisioning new models of community living. And no, because the message was also, as one of the coordinators, John Talbott, put it in his introductory words, to move from a world view of fear about survival towards one of abundance for all. An ecological message appropriately sounded from within the grounds of Eileen Caddy’s foundation, a message which look the grime out of the usual doom and gloom of the subject matter. And, mind you, inside that huge marquee it looked anything but austere with all those chandeliers hanging from a silk-clad canopy.

No, this was not ‘just another ecological conference’. The Findhorn Foundation’s Angel flapped its wings audibly in the background as it embraced Eco-villagers from all over the world, people on their personal paths, ‘political animals’ and social activists, technological visionaries, computer buffs, philosophers and psychologists, all architects of a different future in their own right. And, of course, there was not just a lot of talk, although there was!

Just as community living implies that all aspects of life need to be incorporated and everybody’s unique contribution valued, so most of the Findhorn Foundation Community (employees/residents as well as many from among those in the wider community) were on their feet, pulling their weight, producing tons of wholesome savouries, serving gallons of tea. cleaning loos, with some also contributing their personal gifts like dancing, acting, singing and playing the didgeridoo and other remarkable instruments.

There was time to meditate, to dream-share, to listen to Paul Winter’s earthly-ethereal sounds, to plant trees, go work-shopping and exchange addresses. And for all those who got a bit lost in the proceedings ‘Jolly Joker’ Johnny Brierley kept us right, raising our ‘neolithic’ green spirits and awareness by reminding us of thermal underwear and that eco-friendly act of helping cardboard to decompose by peeing on it (“Lets do it with all those multinational newspapers!”)

Sustainability was the keynote, linking old and sacred wisdom with the latest insights from the scientific front. Peter Russell, who combines theoretical physics and experimental psychology with his study of meditation and eastern philosophies, set the tone on the first evening by directing our awareness from the “utterly cosmic to the utterly personal”—humanity is now waking up to the fact that a shift in perception is necessary, from the outer world towards our inner selves; from a perception

motivated by the fear of lack, which leads us down the cul-de-sac of consumerism, to a perception motivated by love and trust that should lead us into becoming responsible stewards of the Earth and its resources.

Humankind, he suggested, although just “a blink in the eye of God”, is special. As a species, we have had the greatest singular impact on this globe since turning our knowledge one-sidedly towards the kind of technological advancement we currently have, creating the devastating side-effects we must face up to today: a population explosion of now 5.8 billion people, 70 percent of whom live in poverty; the loss of 23 billion tons of topsoil every year; the extinction of an entire species every 20 minutes, to name but a few. But, Russell hastened to reassure us, we are special, also in a positive sense. Through the creation of speech and communication, and the ability to think and look into the future, we have supplied the universe with the necessary tools to become conscious of itself in us.

If you leave it to

the world outside of you to

determine how you feel inside,

then you start worrying, and as

soon as you move into fear you can’t

be at peace. Underneath all that crisis is

a spiritual crisis, telling us that the old

ways of consumerism are unsustainable in

the present day. Ten percent of the world’s

population is raping the rest of the world. We

have to look at the unsustainable conscious-

ness which lies behind that behaviour.

The only person you can change is

yourself. A change of consciousness

is a change of perception. We see the

same thing with a different attitude.

A shift in perception, away from

fear as the great motivator, is at the

root of all the spiritual wisdom

which is now happening—a mass

grassroots movement towards

spiritual awakening.

—Peter Russell

Everything has consciousness, from the smallest micro-organism to the individual cells in our bodies, to ourselves as individuals, groups, communities and all the way ‘up’ to universal consciousness.

While Russell’s focus was the bigger picture, John Todd, creator of the Living Machine, delivered a similar message, but used as his starting point the level of fungi, algae and slugs. Todd’s art, explored through 25 years of research and application, is one of ‘eco-logical design’ which “puts forms of the natural world into a container and asks them to do things like reducing waste, creating food, fuel or compost, self-repairing and withstanding perturbations”; it creates a microcosm held in a climatic envelope that retains heat, lets in light and creates its own independent climate and water recycling. Its bulk is water, (just like the Earth’s) and upwelling currents arc created by putting into this microcosm animals that humans need who, by moving, create oxygen and keep the connection to the land alive. Wind energy is also used, and pumps for circulation. This is an almost self-contained construction, powered by the sun, driven by the ecologies within it and requiring only a small amount of human interference, its ultimate aim being to transform waste back into energy and food.

John Todd showed us a lot of very impressive examples of his work— sewage and water purification plants in Crestone, Colorado, Lindisfarne Hamlet, and at a school in Toronto, Canada (a water-sculpture) and the successful cleaning up of highly toxic land at Cape Cod. He also showed us how the same principles as those now in use to purify waste at the Park can be made use of at sea, as an ‘Ocean Ark’, one of Todd’s future projects.

Environmentally, politically and socially we are, however, not an island in an ocean and, as Rashmi Mayur put it, we must finally begin to accept that “the globe is our home”. Together with Hildur and Ross Jackson, founders of the Gaia Trust in Denmark, Rashmi Mayur, author and lecturer on sustainability and representative of developing world perspectives, organised a meeting of likeminded people at the end of the Conference to discuss what strategies ecologists might implement in connection with the upcoming United Nations Habitat II conference to be held in Istanbul in June of this year. It was suggested that Gaia Trust could set up an ‘alternative conference’ via e-mail while another suggestion was that communities from the southern hemisphere should be encouraged and supported to attend, to enable them to become part of the local people’s movement.

It was agreed that the ecological movement should create as strong an impact as possible on this conference and that one way to gain influence and achieve this would be for as many groups as possible to register as NGOs (non-governmental organizations).

Habitat II will be the last big United Nations conference before the turn of the century, with an expected 25,000 participants. It will focus on the housing of the homeless, but, as Rashmi pointed out, the concept of mega-cities, more urbanization, the illusion of unlimited resources and the ideology of consumption with the world as a market-place, all ought to be challenged as well.

Supporting this, Robert Muller, former UN representative and now Chancellor of the Peace University in Costa Rica, emphasised his belief that the notion and discussion of ‘habitat’ must embrace the entire globe: “Since the 1980s we have entered a period in which the world is number one and humans are number two … The old list of priorities with business first and spirituality last needs reversing.” Muller suggested that a world association of Eco-villages accredited to the United Nations could reach 128 governments. There should be more associations which turn to frugal lifestyles in our developed countries, a de-nuclearization of the planet, a world conference for rural development and demilitarization, and the transfer of the errors of Western civilization to underdeveloped countries should be stopped.

WHY ECO-VILLAGES?

* They are the ideal places for working on the core issue of our times, that of bringing forth the new culture.

* We can’t birth culture simply within ourselves. We need to be able to do it with others.

* We need to do it on a scale that we can understand.

* Eco-villages and sustainable communities are the ‘necessary Yes’ to complement the work of groups like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth who have been part of the ‘necessary No’.ECO-VILLAGE DEFINITION:

* It’s on a human scale.

* It’s a full-featured settlement—not just a housing development, businesses or agriculture, but all of those things, and more.

* It’s a place where human activities are harmlessly integrated into the natural world, also in a way that is supportive of healthy human development.

* It can be successfully continued into the indefinite future.ECO-VILLAGE BUILDING BLOCKS:

* The physical layer, the layer of biological systems: waste water treatment, food production, fuel, animals, all of those things.

* The built environment: buildings, roads and the other parts that we humans not only like but really benefit from, which help us to flourish.

* The human part: economic systems and governance and the community ‘glue’—spiritual, emotional, cultural—that which enables a community to pull together through the inevitable rough spots.CHALLENGES:

* “Which leg of a three-legged stool holds it up?” At a global level, we need to effect changes simultaneously in all three areas of technology, consumption and population; we need to learn how to combine: our relationship with the natural world around us (environmentalism), our relationship with each other (politics and social issues) and our relationship with ourselves (health, personal growth, spirituality); we need to balance the heart, the mind and the will.* It’s a ‘whole system’: we are having to do it all at once. We’re having to deal with all of these issues at the same time as we are having to face challenges e.g. in our relationships and with our kids.

* We discover that those great ideas we had that we thought solved the problems of the world are only a part of what is needed.

* Need to balance group and private, what needs to be done today and planning for tomorrow, ‘hardware’ (physical) and ‘software’ (human) aspects.

* Need to balance learning styles and personality types which is a level of diversity beyond cultural, gender, racial diversity (Are you the kinesthetic type? Do you need to ‘get it’ in your body—do you hear it, do you see it? Or are you the verbal type?)

Robert Gilman

Antonella Verdiani, representing UNESCO, the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, pointed out ways of making positive use of what the big organisations have to offer, quoting as an example the ‘Planet Society’ programme which aims to create an international exchange network to “advance mutual knowledge and understanding” between individuals and groups committed to creating sustainable development throughout the world.

“There’s only one kind of economy you can ever make sustainable and that’s your own local economy.” Guy Dauncey, eloquent consultant for sustainable communities in British Columbia and Arizona, and director of the Institute of Social Inventions in London, led us into a guided meditation in which we were to visualise our own local community becoming the place of our wildest dreams. On emerging from this, he then helped us to visualise what significant changes might take place in this, the Moray Firth area, via twelve giant steps, between now and the year 2015.

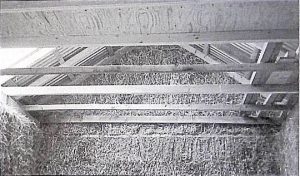

- Straw bale house outside

- Straw Bale House inside

Using the Internet, a group of people would collect the necessary information about what is going on ecologically and socially around the globe and feed this back to those local people interested in creating a sustainable future. This would help them understand that every act of economic growth is accompanied by an equivalent act of ecological loss; that non-renewable resources are heading for a plunge and ‘business as usual’ will inevitably result in the phenomenon known as ‘overshoot and collapse’. At the same time they would become aware of the incredible wealth of initiatives worldwide which are being mobilised to counteract this disastrous course of events.

In trying to re-think the economy, they might look, for instance, at a watch. They would realise that it is created not just out of the physical resources it consists of, but also intelligence and that, unlike physical resources, the growth of intelligence is unlimited. So that a reversal of the present situation might envisage a reduction in resource use while at the same time encouraging the continued exponential growth of intelligence.

Getting down to the brass tacks of tackling local issues, with the help of information on the Internet, a local group would, for instance, create a political lobby to change the government’s environmental legislation and taxation, create a Regional Green Plan with five year goals to include a reduction in pollutants and increases in energy efficiency, retrofitting of houses, radical changes in public transport, re-vamping of urban design; they’d reshape employment policies by reducing the weekly working hours, initiate community businesses and banks to emphasise local trading, encourage permaculture and local organic food production, link farmers with each other through ‘veggienet’. They would emphasise the role of new technologies such as solar-hydrogen vehicles and houses becoming totally self-sufficient for their sewage, water and electricity; they would find ways of moving mainstream medicine away from its focus on controlling sickness towards encouraging wellness; while locally, people would begin to experience themselves as part of an organic whole by defining their area through the existing watershed, enabling them to create their own bioregional reality.

- New, home-made ‘bird boxes’ – low- energy compact fluorescent outdoor lighting. The lights use an 11 watt bulb and save more than £50 pa in costs over a conventional light.

- Electric distribution boxes, again home-made. The Foundation has its own private electrical system, 20 per cent of which is supplied by its own windmill.

Because realistically none of these initiatives would go unchallenged, Dauncey also included in this scenario the inevitable counter-moves which would come in the form of false information backed by multinational and other concerns and the need to embed local political changes globally, for instance through the creation of a global code of environmental conduct or a total shift in taxation from lax on earnings to ecological taxes.

As much as his display of the hypothetically feasible was entertaining and interspersed with drama, this was not ecological science fiction: most of the information provided was based on initiatives that are already putting these suggestions into practice. Impressive it was, to see how all of this could happen in just one area like the fictional scene of the Moray Firth region. In Dauncey’s scenario, fifteen years on people would experience that their culture would have shifted from technologies of matter to technologies of light and nature: again the embrace of advanced technology and the move ‘back to nature’, but this time in the full awareness of nature’s inner wisdom.

Be out there, get involved in local, national and international politics, was the call voiced by quite a number of the speakers, some of whom added a note of warning not to invite critics in too early by broadcasting innovative ideas when they are still in a fragile state. Eco-vil lagers tend to be isolationists, said the American speaker Bob Berkebile, who challenged us with a bit of arithmetic: we were 400 participants, each of whom might represent 500 others. In relation to the global population of 5.8 billion people, with its 250,000 increase every day, we represented a percentage of a mere 1/3000 of 1 percent of the total world population. However,

Never doubt that a small group of

thoughtful, concerned citizens can change

the world. Indeed, it is the only

thing that ever has.

—Margaret Mead

Jill Jordan, from Maleny, a small community in Queensland, Australia gave some helpful techniques for how we can involve the local population in what we are doing: give a lot of information, allow people the space to change their minds; people want to help, ask for it; join the local organisations; build on existing agreements rather than putting all the attention into areas of disagreement (90 percent of issues are common points, do these first, build trust, then deal with the controversial 10 percent); keep an open heart, acknowledge and try to understand why there may be fear and find strategies to overcome it; don’t be side-tracked: when 20 percent of the population have seen a good idea, it is unstoppable.

Jordan is a community development consultant who, since moving to Maleny in 1970, has helped to start many highly successful community initiatives: a bulk health food co-operative, a Credit Union, a LETS system and ventures like the Maleny Waste Busters Community Co-operative (which re-uses electronic goods, bicycle parts etc.), created in 1989 as a joint venture with the local council. They have also started a co-operative club/restaurant, a community radio station, a forest growers group, an arts co-operative, a women’s co-operative, a co-operative learning centre for all ages and a tribe community organisation to help aboriginals find outlets through which to sell their produce. Another venture is a special rural task force for the sustainable use of land which enables the community to buy significant pieces of land which it does not want the local council to develop.

She described how the community development process can evolve—that new strategies must arise out of a real community need, the process must be inclusive, available to everybody; it’s important to have clear objectives (don’t over-reach), use role models, develop support networks, skill build (especially interpersonal skills and conflict resolution), embed strategies in the wider community (get representatives onto the local council) and have a ‘mother’ to hold and nurture projects in their infancy (someone who is also then able let go, when appropriate).

Another speaker with a good background of experience in community living was Glen Ochre, from Common Ground, another community in Australia, founded 14 years ago. She provided participants with a bucket full of ‘community glue’, filled with card-board paper hearts which read Love, Trust, Clarity, Courage, Fun, Patience and so on, a colourful assortment resembling the good old Findhorn Angel cards which was cheered happily by the audience. Her emphasis was to highlight that if we are seeking to build a more co-operative, sustainable world, then it is important to start with that essential ‘community glue’—our relationships with each other. Her work consists mainly of supporting communities to resolve their conflicts.

Our socialisation has made us

become disconnected to anything below

our necks; only the intellectual is

accepted. Everything else has to be

repressed into the unconscious, as it

would damage us in a world that does

not honour or celebrate anything below

the intellect. IPc need to allow our

hidden agendas to come to the

fore and understand the stuff in

the unconscious when

living together.

—Glen Ochre

She would like to see us living more intimately, more closely together, raising our children collectively. She believes that a lot of healing can take place in groups. For example, parent-child dynamics are often re-enacted in group settings but “when this is dealt with appropriately, miraculous things can happen.”

The participants listened awe-struck to yet another phenomenal account of innovations and communal activities—those set into action by the now 25 year old community The Farm in Tennessee. Long-term member Albert Bates gave an eloquent account of this initially mobile hippy community who gave birth to their first children while still ‘trucking’ in tattered old buses, giving rise to some of their women becoming very successful natural birth midwives; of the communards’ need to buy the cheapest land available to settle down and start a self-sufficient, if simple, life in Tennessee; of producing their own food and transforming their old buses into houses by degrees, with the help of building materials from dumpsters; of their engagement in earthquake-shaken Guatemala, where they sent carpenters and set up factories for prefabricated buildings; of their withdrawal from their social engagement with the Guatemalans when they realised that the oppressive government of the day had begun to persecute their protégés; and of their many other strands of production and engagement, such as starting up a free ambulance system in the South Bronx, growing mushrooms, producing tofu, creating a business with radiation detectors and much more.

Helena Norberg-Hodge

We also heard the very touching report of a one-woman-back-to-nature quest, the personal experience of a loving and sustainable lifestyle as it still exists in the Himalayas: Helena Norberg-Hodge who has spent almost half of every year in Ladakh for the past twenty years, has created an organisation to help the local population sustain their old way of life and yet ease it by creating solar energy and small hydroelectric installations; she is also trying to give the Ladakhis a more realistic perspective of the Western lifestyle to counterbalance the negative influence of the media, manipulated by market forces, on their own culture and lifestyle.

At the other end of this vast spectrum of community building is Auroville, its story told by member Marti Mueller. Incredibly diverse, it is home and workplace to one thousand people from over 35 countries who work in close partnership with the local people. Since its beginnings in 1968 the initially totally devastated land with nothing but eroded laterite soil has been transformed into an exciting centre of ecological and spiritual exchange. That process was begun by large scale reforestation, carried out with a lot of educational input, the initiation of organic farming, recycling of water, health work, village empowerment work and the creation of businesses. It has now reached the stage of outreach work.

Closer to home Peter Harper told us about the life and work of CAT, the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales, and there was a large variety of workshops to choose from, presenting fledgling Eco-villages, not yet part of GEN (the Global Eco-village Network), such as the Okodorf movement in Germany on the former border with the East, or well-established communities such as the one at Lebensgarten, represented by architects and environmental activists Margrit and Declan Kennedy. A list was also circulated gathering together people interested in creating an Eco-village, intended to house a thousand people, either in Southern France or Northern Spain, a project being instigated by Gerald Morgan-Grenville, one of the founders of CAT and then there were other workshops on communities from all over the world.

Another strand in this colourful tapestry of sustainable living was the need to develop a more wholesome and sustainable lifestyle in the cities, through co-housing and other creative ways of integrating new ideas into a mainstream setting. Permaculture featured high on the list, both for rural and urban visions of a healthier and more holistic way of life.

We shape our dwellings, and

thereafter, they shape our lives.

—Winston Churchill

A lot of inspiring examples were shown by architects, urban planners and landscape designers—slide upon slide of interesting solutions to achieving the necessary balance between our needs for intimacy and privacy versus interaction and exchange, the natural symbiosis of humankind and nature, a healthy interaction and co-existence of people of all age-groups, and all of this interfaced with lots and lots of solar panels.

One slide showing a ring of African mudhuts around a wide open space stood for a lot of these aspirations: “This is ultimately what we are striving towards,” the presenter said. Another slide showed us the wrinkled faces and crumpled coats of four or five old Italian men sunbathing and chatting on a park bench in New York City—this bench, we were told, is of vital importance! A powerful tool for accessing our own inner knowledge was introduced by Clare Marcus, professor of Architecture at Berkeley, California, in the form of a guided meditation in which participants were guided back to the original dwelling of their childhood. Marcus claims that, “The environment of your childhood stays with you, subconsciously, for the rest of your lives.” We were also asked to think of a time when we were very upset and then asked, “Which place helped you to get out of it, which place made you very happy?” In Marcus’ experience, 80 percent of people remember this place to be somewhere out-of-doors, in nature, with swift moving clouds, the rippling or stillness of water, the wind rustling through the leaves. Patients in hospitals recover much faster from their illness when their windows allow them to look into trees.

During the week, the celebration of age old rituals and the tapping of ancient wisdom co-existed happily beside the application of the most advanced ideas in modern technology and science. A wonderful openness towards considering either end of the spectrum and an underlying understanding of the need to combine both was perhaps one of the most inspiring elements of this conference.

Peter Dawkins, who has developed the ‘Science of Life’ or ‘Zoence’ which puts old knowledge and spirituality into architecture, spoke about the notion of landscape temples and the healing of the earth and its people through geomantic awareness. He believes that humankind was created to be the gardener of the world and sees the landscape, like us, being composed of patterns of energy. He showed how cathedrals have been built using the model of three main bodily locations and seven chakras, just like the human body, explaining that the energy flow through this body creates polarities that enable manifestations to occur; it is the opposites rather than energies of a similar kind which are most creative. He believes the landscape is the foundation of everything else: if we get it right, the landscape enjoys it. Dawkins encouraged us to “Celebrate where you are, then miracles, coincidences, occur,” warning that the abuse of a landscape mentally, emotionally and physically, produces a negative aura which subtly affects us, in the same way that celebration and right relationship to the landscape can create a positive atmosphere.

Inside the earth lodge constructed during the conference

While out of doors on a mound in the Park May West, Craig Gibsone and a group of participants congregated to create a brand new ancient site in the form of an Earth Lodge, back in the Universal Hall, ex-installer of the Foundation’s Macintosh link-up Stephan Wik introduced himself to his old community as webmaster of the Gaia Web Project. Born out of the need to network the local initiatives of communities all over the world to help them make an impact as well as give each other support and advice, GEN (the Global Ecovillage Network) was created by Gaia Trust and makes use of the creative and community-building properties of the Internet to keep members in touch with each other.

GLOBAL ECO-VILLAGE NETWORK (GEN)

Eco-villages are in essence a modern attempt by humankind to live in harmony with nature and with each other. They represent a ‘leading edge’ in the movement towards developing sustainable human settlements and provide testing ground for new ideas, techniques and technologies which can then be integrated into the mainstream.The need for developing sustainable human settlements relates directly to the commitment by the world leaders at the Earth Summit in Rio (1992) to programmes that will move humanity to sustainability in the 21st century (Agenda 21). To achieve the goals of sustainable human settlements, there is a need for pilot communities and for an exchange of information between them and the mainstream.

The Global Eco-village Network (GEN) is in the process of expanding. Three regional offices are located in Australia (Crystal Waters), USA (The Farm) and Germany (Lebensgarten). The offices are based in communities who have been part of the seed group which initially consisted of: The Findhorn Foundation (Scotland), Lebensgarten (Germany), Ecoville Nevo and Rysovo (Russia), Gyurufu (Hungary), Crystal Waters (Australia), The Farm and The Manitou Foundation (USA), the Ladakh Project (India) and the Danish Eco-village Association.

These projects represent eco-villages at different stages of development, the oldest established more than 25 years ago and the most recent being under establishment. Most of these projects are internationally well recognised, while the projects in Eastern and Central Europe are in the start-up phase.

Common to all of the projects is their focus on education and a desire for the integration of ecology, spirituality, and community and business development. Each of the projects functions as an eco-village training centre for their area. The range of skills that are on offer is very extensive, covering all aspects of sustainable community living.

The following programme areas are specifically being developed by the eco-village network:

* Establishment and development of eco-villages.

* Eco-village Training Centres and Outreach programmes which offer the potential of further developing and informing on the shift from high consumption lifestyles to more satisfying, high quality, but low environmental impact lifestyles and social structures.

* Development of Sustainable Technologies and Businesses which is a prerequisite for the economic sustainability of these projects.

* International Networking enabling eco-villages to rapidly increase their knowledge through the sharing of information, work exchanges, training and outreach. A special emphasis is placed on youth training and exchange.

* Fund-raising.For further information contact the GEN International Secretariat at: Gaia Villages, Skyumvej 101, Snedsled, 7752 Denmark. Tel: +45 9793 6655, Fax: +45 9793 6677, E-mail: gen@gaia.org, Internet. World Wide Web: <URL:htlp://-murw.gaia.org>

GEN began, as co-founder Ross Jackson from Gaia Trust explained, around 1987, with the start of Gaia Villages and the Gaia Technologies Project, both of which answered a need for the exchange and implementation of good ideas which support the concept of sustainable living. It enables the exchange and tapping of resources in the fields of job-creating, the setting up of‘green’, ecologically as well as economically viable businesses in the areas of food, energy, housing, banking, health and communication. Jackson explained that when Stephan Wik introduced them to the world of the Internet as a mainstream, low-cost medium of communication worldwide, he and his wife took to it readily. In particular they liked the fact that its use seems to alter the normal power structure: there are no middlemen, we are in direct contact with each other.

As Wik explained, this network of information is indestructible as it is in constant flow; it is democratic and non-profitmaking as it is owned by nobody and no single market or political force can, as he put it, take over and manipulate its contents. It is about giving information freely, as used to occur within closed groups such as those of scientists who would exchange information about their research. It has nothing to do with the old ideology of getting—profit-making or marketing.

Listening to Wik’s enthused statements about the potential of the World Wide Web you could, indeed, have been mistaken about the subject matter— what looked like a computer complete with screen, keyboard and lots of unseen megabytes to the ordinary user of the tool became, through his description, a highly sophisticated yet utterly easy-to- use and truly democratic vehicle for spirituality, love in action, in our daily lives. In tapping in through the Internet to the wealth of information that exists all around us we could be said consciously to be recreating on a smaller, technological scale, the intuitive and spiritual networking processes which we indeed are capable of when we tap intuitively into universal knowledge.

Something new is happening

to the whole structure of human

consciousness. A fresh kind of life is starling.

Driven by the forces of love, the fragments of

the world are seeking each other, so that the

world may come into being.

—Teilhard de Chardin

A long queue of people squeezes through the door of the marquee, sorting through the latest torrent of information in exchanges with fellow information-battered participants. The tea- and-coffee-serving volunteers in the marquee are in full action, ready to receive the masses, teapots in hand; biscuits and cakes on trays have been set out on gleaming white table cloths; conference organisers have filled the information corner with sheets and sheets of workshops still to come with the exhortation for us to fill our names in.

This time the conference organisers, needing assistance with the practical chores and, at the same time, not wanting to turn anyone away from these inspiring talks and workshops, offered anyone from within the Foundation and its wider community the opportunity to participate in exchange for work, on an hour for hour basis. Those willing to scrub floors or peel dozens of onions for lunch were rewarded with the opportunity of listening to a speaker or attending a workshop of their choice.

During the breaks, participants also felt the need at times to congregate around ‘special’ tables to discuss particular concerns or they could join their fellow countryfolk, relaxing into their own language. Last, but by far not least, people could relax into less mind-boggling activities, free their stiffened muscles through dancing or acting, let out some liberating songs with choir-leader Kate O’Connell, wander off to ancient sites and whisky distilleries with Sandy Barr, crawl, kids first, into Peter Vallance’s tipi on the Foundation’s newly acquired ‘Field of Dreams’ to hear a story around a crackling fire, follow him to a ritual at the Clava Cairns, get a gentle rub or vigorous massage from the health care group or enjoy a hands-on paper making workshop, pulping up old shreds for new sheets.

There was so much on offer during this event, it was easy to become overwhelmed. No wonder that this relentless stream of information—from slugs to sludge to slums to space to cosmos, and from ancient to futuristic, from urban to rural, from political to personal, spiritual to technological—eventually left its mark on participants’ dreams. Every morning Joan Wilmot and partner Robin Shohet held an open 5 minute space in which people were invited to share their latest dreams. Fascinating it was, though, this exercise in dream monitoring, as it showed how the individual reflects the input of the larger group, merging together at last into powerful images of a glowing, wondrous and sparkling planet Earth.

***

Carola Spleltstoesser is a freelance journalist who has recently joined the One Earth team and who lives with her family at Woodhead, a small community close to the Findhorn Foundation.

Guest Authors are contributors who are not COIF members (for various reasons).

Leave A Comment