Editor’s Note: This post gives a short report of the archaeological study undertaken on the Sanctuary site, as well as the full study in the form of a pdf flip-book and full searchable text.

During preliminary groundworks for the construction of the new sanctuary, the mechanical excavator exposed a shell deposit at the east end of the site. After being notified of it, I offered to investigate further, which led to several days of excavations. These revealed that there were in fact two shell middens, one on top of the other, and separated by approximately ten centimetres of wind-blown sand. The presence of charcoal and fire-cracked stone indicate that these were not merely piles of shells, but rather the result of human activity—the collection of shellfish from Findhorn Bay, and their subsequent cooking and eating.

I assumed that these would prove to be Mesolithic, at least six thousand years old, and therefore created by our hunter–gatherer forebears. But I would not know for certain until the results of radiocarbon dating came back.

In the meantime I dug down through the midden deposits, took photographs, and collected numerous samples of the shell and other material. These samples were examined carefully in the hope of finding charcoal, seeds, fish bone, and with luck some cultural objects. These objects might range from small flint tools, to antler tools, and harpoons.

Cockles, as can be found today in Findhorn Bay

The analysis of the samples showed that the upper deposit consisted largely of mussel shells, sand, and charcoal, while the lower one was dominated by cockle shells and fire-cracked stone. The differing assemblages of shells may indicate a difference in the preferences of the two groups using the site, or they may represent changes in the shellfish in the bay over time, as some species are sensitive to changes in temperature and the composition of the substrate. Similar differences were observed in middens on the Culbin Sands in excavations there.

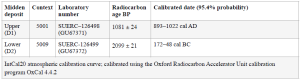

It would be an understatement to say that I was surprised by the radiocarbon dates when they came in. It turns out that neither deposit was Mesolithic. The lower one dated to the later Iron Age – between 172 and 48 BCE. This is a time in Scotland when many defended hill forts were occupied, as were the Broch towers in the North, and iron smithing was being carried out in the enclosure on Cluny Hill in Forres. The upper midden deposit dated to the Early Medieval period (893–1022 AD), about a thousand years later than the lower one, about the time when the Pictish fort at Burghead was burned, and Sueno’s stone was being erected in Forres.

Acknowledgements: Thanks are owed to Jonathan Caddy, who alerted me to the presence of the shell midden deposits; to Bruce Mann of the Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service who supported the project and funded the radiocarbon dating; and to Jason Caddy of Greenleaf Design and Build who gave me access to the site and made the excavations possible.

Image on top: Michael Sharpe during the excavation of the middens

***

To browse the report please use the < > arrows at the left and right of the window. For easier reading, use the buttons at the bottom of the window: use Zoom (the + and – buttons) or Toggle Fullscreen (the four arrows pointing outwards).

***

Full text of the report – Please click on the arrow on the left to expand the sections.

Abstract

An archaeological rescue excavation was carried out on a shell midden which came to light during preliminary groundworks for the construction of a meditation sanctuary at 46, The Park, Findhorn, Moray. The midden is situated on a raised beach near Findhorn Bay. It consisted of two deposits of differing character separated by a layer of blown sand, suggesting two different phases of occupation. The upper deposit was largely mussel shell fragments with abundant charred wood and occasional fire-cracked stones. The lower deposit was rich in cockle shells, and fire-cracked stone, but contained little charred wood. The lower deposit also contained a number of struck pebbles and perforated cockle shells. Radiocarbon dating of small diameter roundwood from the two midden deposits returned dates of 172–48 cal BCE (95.4%) for the lower midden, and 893–1022 cal AD (95.4%) for the upper midden.

Introduction

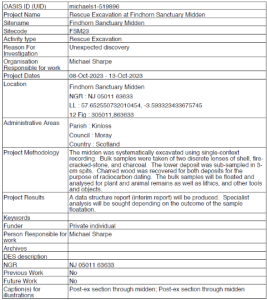

This midden deposit came to light in early October 2023 during preliminary groundworks for the construction of a meditation sanctuary at 46, The Park, Findhorn, Moray (planning No 22/01674/ APP). While the digger was scraping the ground at the east end of the site and digging into the adjacent earth bank, deposits of shell were observed by a local resident and reported to the author. This was an informal communication, as no archaeological oversight had been required for this development. The author offered to excavate the midden as a contribution to the project, which was replacing a meditation sanctuary that had recently burned down.

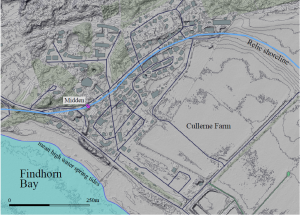

Illus 1: Site location Location maps, Ordnance Survey Open Data.

Illus 1: Site location Lower map reproduced from Moray Council planning Reference 22/01674/APP document

Site location and description

The midden is located at NJ 05011 63633, approximately 80m to the northeast of the Kinloss to Findhorn road (B9011), in the southwest corner of the Park Ecovillage, and 160m from the shoreline of Findhorn Bay (Illus 1). The upper midden surface lies at approximately 0.6m below the road surface immediately to the north which lies at 7.6m AOD (Above Ordnance Datum). In a LiDAR survey of the area (Scottish Remote Sensing Portal) a relic shoreline can be made out. Though now mostly disturbed by development, it consisted of a raised beach of sand and water worn pebbles at approximately 8m AOD, dating to some time after the Post Glacial High Sea Level, which Shennan et al. (2018) place at 6.5m above the current level of 2m. This higher relative sea level (RSL) created an enlargement of Findhorn Bay into what is now Cullerne Farm, and the Park Ecovillage.

Illus 2a: 1m LiDAR of the area around the midden showing the relic shoreline consisting of a raised beach (Scottish Remote Sensing Portal)

The bedrock consists of the Forres Sandstone Group dating from the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, but in this area is only present at a depth of about 60 m. The surface geology is Raised Marine Deposits of Holocene Age: sedimentary superficial deposits of sand and gravel formed between 11.8 thousand years ago and the present during the Quaternary period (NERC 2024). A parallel series of raised beaches, oriented roughly east–west, composed of sand and gravel, stretch from the midden site northwards to the sea. The midden was situated on one of these.

Archaeological background

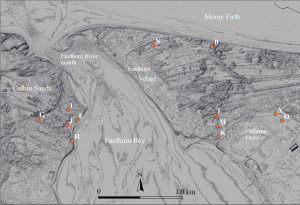

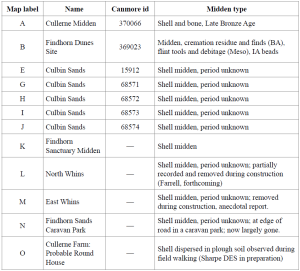

Illus 2b: Middens on the shore or near Findhorn Bay discussed in the text. The base image is a digital terrain model (DTM) of 1m resolution with 0.5m contours (Scottish Remote Sensing Portal)

Possibly the earliest reference to middens in the area was by George Black (1891) who undertook an archaeological examination of the Culbin Sands, at the time a broad expanse of sand dunes and shingle ridges to the west of Findhorn Bay, which is now largely forested. He discovered numerous “shell heaps” scattered about Culbin, including on the western shore of Findhorn Bay (Illus 2b sites E, G, H, I, J) and also on the Findhorn Village, or east, side of the bay (Illus 2b, possibly sites B and N), although he does not include these latter ones on his map. One of the few that is readily identifiable today on the west side of the bay is Black’s site No 1 (Black ibid, p. 486, and map, here site H). On a recent visit, the author noted shells, fire-cracked stone, and flint tumbling down this bank, though evidently much of the deposit Black observed has since been lost to erosion. These shell heaps typically contained mussel, periwinkle, and cockle shells, and a few also contained oyster or scallop. Several of the shell heaps contained a hearth and “carbonaceous matter” at their centres. Black was not in a position to date these middens, other than through their associated artefacts. Some were likely Mesolithic, while others were clearly of Bronze Age date. A phenomenon common on Culbin Sands has been the erosion by wind of the shell heaps and old land surfaces which in places has resulted in the tumbling down together of once stratified deposits, and thus the loss of information about phasing.

Table 1. Middens shown in Illus 2b

On the east side of the Bay, Black lists several shell heaps east of Findhorn Village that have likely been lost to coastal erosion (approximately 45m of coastline has been lost since World War Two alone), as only one shell heap/midden has been observed east of the village in more than 20 years of field walking this area by the author (site B). However, some of these may reappear as coastal erosion continues and the dunes continue to change shape. In November 2023, following a storm during high tide, a probable wartime deposit of charcoal and bottle caps was recently uncovered at the coast edge overlain by 2m of blown sand. Similarly, some of an old land surface dating to the Bronze Age is currently obscured by 6–8m-high sand dunes. One midden and associated archaeology at this location is described below.

Other shell middens have been uncovered in the last two decades during construction work (Illus 2b sites L, M and, this site, K).

One known midden on the east side of the bay (Site B) has been recorded as a component of a complex, multi-period site a few hundred metres east of Findhorn village (Moray HER NJ06SE0010; Canmore id 369023). Prior to its survey and the surface collection of artefacts it contained the scattered and fragmentary remnants of at least one Bronze Age cremation with grave goods (burnt bone, copper alloy objects, a flint strike-a-light, faience beads, sherds of decorated beaker); Iron Age beads; sherds of a steatite vessel; and a substantial quantity of pot sherds. A large scatter of flint debitage and worked items includes: flint thumb scrapers; grey flint that may be Yorkshire flint imported in the Neolithic (Torben Bjarke Ballin, personal comm.); and probable Mesolithic microliths. This site may be the same one Black (ibid, p 493) mentions where he found cremated human bone. His guide reported that stone axes and other artefacts had been found over the years. This multi-period site likely began as a Mesolithic midden.

The continued harvesting of shellfish in the area was confirmed by the discovery and excavation of a late Bronze Age midden on Cullerne Farm, one kilometre south of the village (Moray HER NJ06SE0108; Canmore 370066.). This contained mussels, periwinkles, cockles, and broken animal bone. Callander (1911) reported seeing large numbers of “kitchen middens” across the Culbin sand dunes, many of which had been disturbed by collectors. Some of these contained oyster, cockle, periwinkle, and animal bones as well as pot sherds and flint.

In recent decades at least one midden excavation has been carried out on the Culbin Sands using modern archaeological methods and dating. Coles and Taylor (1973) excavated a midden in the central part of Culbin, and concluded that it had “represented temporary occupation by a small group of people of an area not well-suited for intensive cultivation or animal husbandry”, dating to the mid to late Bronze Age (Coles and Taylor ibid p 98). In addition to animal bones, the midden contained mussel, cockle, and periwinkle. Notable were changes in the species assemblages over time, preserved in the stratigraphy in the midden. In the lower midden cockles were an important component of the food supply, whereas in the upper midden they were barely present, being replaced by mussel and periwinkle. They propose that the changing relative quantities of the various species could be due to “over-exploitation of the cockle-beds, changing economic preference, or changes in the littoral environment”. They suggest that changes in the coastal environment were the likely cause of the cockles’ later disappearance from the midden, as they are vulnerable to changes in substrate particle size.

Aims and objectives

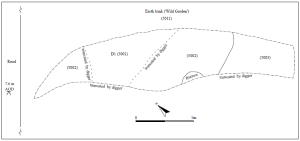

This was essentially a rescue excavation on a development site where archaeological oversight had not been a requirement of the planning permission. The aim was to record as fully as possible the nature and phases of the midden. The principal objectives were to obtain dating evidence: either charred material for radiocarbon dating, and/or diagnostic artefacts. Illus 3 and 4 show the midden after an initial clean, and prior to excavation.

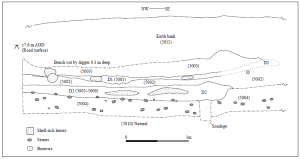

Illus 3: Pre-excavation plan of midden

Illus 4: Pre-excavation section of midden

Methodology

All archaeological work was carried out in line with the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA) Code of Practice and Standards and Guidance, and in consultation with the Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service.

Excavation

Excavation took place from 08–10 October 2023, using hand tools and single context recording.

Illus 5: Post-excavation section of midden

The midden was likely truncated at its western edge when the original sanctuary was built, and possibly also by the road to the north when it was constructed, likely during the last war. The post-excavation section (Illus 5) shows that the midden extends an unknown distance into the area to the east known as the ‘wild garden’, which has been left largely untouched by the gardeners for several decades. The deposits were overlain by a redeposited mix of soil and rounded pebbles, up to one metre deep, which was likely deposited when the original sanctuary construction took place in 1968, and/or when the adjacent road was built. The Park Ecovillage contains the foundations and upstanding remains of several structures dating to the war including a bomb shelter.

After initial cleaning, the midden was photographed and drawn in section and plan (Illus. 3, 4). It was then excavated by hand and sampled.

Most of the unsampled material in the deposits was sieved on-site to check for small lithics, bone, etc.

Recording

Sections and plans of the midden were hand drawn on Permatrace at 1:20 (Illus 3–6), and photographed with a DSLR in RAW format. Contexts were recorded on paper forms (Appendix 1).

Illus 6: Post-excavation plan of midden and site location (scale bar only applies to midden outline and details)

Results

Archaeological features

The midden consisted of two deposits of differing character— D1 and D2— separated by a lens of pale blown sand (5002) (Illus 5). Context (5004), the lowest at the site, is a buried land surface which developed on a raised beach of sand and shingle, upon which the midden was established.

Deposit 1

This truncated deposit (context 5001) measured 1.5m long by 1.0m wide, and was .012m deep, but as can be seen in the post-excavation section, it was originally at least four metres long. The deposit is characterised by its near black colour, predominantly mussel shell fragments, rare cockles and periwinkles, and abundant charred wood remains. It also contained occasional fire cracked stone (FCS). There were several small shell-rich pockets within the deposit. Below this deposit was a layer of fine pale sand (5002) up to 0.2m deep, assumed to be blown sand, sealing deposit D2 below.

Deposit 2

This deposit (contexts 5005–5009) measured 3.3 x 1.0 x 0.15m deep and was dominated by cockle shells and sand, with only rare mussel and periwinkle, and one small clam, with rare charred wood fragments. It was excavated in five 0.03m spits. The only discernible difference between the spits was that FCS was common in the lower two spits and rare in the upper three. This deposit also contained several concentrated pockets of shell.

Buried land surface

Context 5004 is the buried land surface upon which the midden D2 was deposited. It consists of a stony soil of 0.4m depth, that developed on a raised beach deposit, and contained occasional FCS and rare fragments of charcoal, but virtually none of the shell of D1 and D2, only a few fragments that likely worked their way down from D2 through bioturbation, including burrowing. (The ability of burrowing to relocate material was demonstrated by an early 20th c bottle base being found in context 5002, the blown sand layer). Context 5004 was not completely excavated, as it was not considered an anthropogenic deposit. A sondage was cut through it to ‘prove’ the ‘natural’ below.

Environmental samples (Appendices 7, 8)

Five bulk samples were taken—one from D1, three from D2, and one from (5004), the lowest context. Material removed but not collected was sieved on site to check for artefacts—lithics, bone, and antler, etc. Samples were wet-sieved with a 5mm diamond pattern sieve in order to remove the fine sand and shell fragments, as an initial test showed that the sediment was too wet to recover organic material through flotation (Kenword et al. 1980; Struever 1968). The dried retents were inspected for artefacts, bone, antler, charred wood, etc. Sub-samples of charred wood were selected for the purposes of radiocarbon dating from contexts (5006) and (5009)—spits within D2.

Small grab samples were also taken during excavation of charred material in the lowest deposit (5004), and from the surface of D1. A grab sample was taken of the presumed blown-sand layer (5002).

Detailed descriptions of each sample can be found in Appendix 7, and of the charred wood in Appendix 8. There were notable differences between the two midden layers. The D1 bulk sample was dominated by charred material and shell fragments—mostly mussel, but also containing a few cockle and periwinkle. Samples from the upper two spits of D2 (D2A, D2B) were dominated by cockle shells, both whole and fragmentary, and had little charred material or FCS. The samples from the lower two spits (D2D and D2 basal) were similar to the upper two, but for FCS now being frequent. The middle two spits of D2 were not sampled, but were sieved on site. Illustrations 15 and 16 show the different nature of the material in D1 and D2, respectively.

Illus 15: Charred wood and shell fragments from the upper deposit D1 (5001), (photo 59).

Illus 16: Cockle shell from lower midden deposit D2B (5006), during processing of samples (photo 54).

Shell

Species of shell present in the midden, and referred to by their common names, were: cockles (Cerastoderma edule), mussels (Mytilus edulis), and periwinkles (Melarhaphe neritoides). The taxonomy of the single clam present is unknown.

Finds assessment

Lithics

Eleven apparently worked stone artefacts were recovered during excavation and from the bulk samples (Appendix 6; Illus 12–13). Seven of these are small pebbles which have been struck once or repeatedly to remove flakes of stone. One appears to be the remainder from the process of producing a truncated discoidal flake (a tool type found in great numbers by the author throughout the Findhorn dunes area, and in archaeological contexts at several sites; Sharpe, in preparation).

Another is a sharp-edged flake of stone struck from a pebble. The two remaining are larger near flat stones which have been similarly struck to produce flakes. The stone types include quartzite and sandstone.

Illus 12: (L–R) Small finds 401, 402, 403, from contexts 5005, 5004, 5001,

respectively (photo 51).

Illus 13: Clockwise from upper left: small finds 409, 405, 407, 410, 406, 404, 411. All from context 5004 (photo 52).

Perforated shell

Twelve perforated cockle shells were recovered from samples in deposit D2 (5005) (Illus 14). On seven of these shells the perforations were relatively small and in the region of the hinge. However, the perforations of the other five are much larger, and, judging by the stepped pattern of the breakout, appear to be the result of an impact on the inside of the shell. It’s notable that cockles found on the nearby foreshore frequently have similar perforations near the hinge.

Illus 14: Perforated cockle shells from context 5005: small find No 412 (photo 53).

Radiocarbon dating

There was sufficient small diameter charred round wood from secure contexts to date the two discrete midden deposits (Appendix 8). This includes material from the surface of the upper deposit (D1, sample No 001), and from the lower deposit (D2, sample No 012). Subsamples of these were submitted for dating to the SUERC Radiocarbon Laboratory at the University of Glasgow.

Radiocarbon dating results (Appendix 9)

Discussion

The radiocarbon dates indicate Late Iron Age and Early Medieval use of the site, separated by a gap of about a thousand years, and a deposit of wind-blown sand. These represent only the third and fourth dated midden deposits for the dunes complex on either side of Findhorn Bay, the first being Coles and Taylor’s (1973) excavated midden at Wellhill, Culbin Sands, dating to the Bronze Age (1669–1285 cal BC), and the second being the Late Bronze Age midden (1205–1016 cal BC) at Cullerne Farm, 700m to the northeast (Sharpe 2021). The Cullerne midden was likely at the southern margin of the dunes area at the time of its establishment.

The majority of the known middens on the Culbin Sands to the west of the bay are now lost to us – eroded by the sea, buried by sand, obscured by plantation forest, or robbed out by collectors seeking prehistoric objects, for which the Culbin Sands were well known, and have not been dated. And all but one of the middens reported from the east side of the bay are similarly lost, though likely through coastal erosion and ablation. And we don’t have dates for these.

The shell assemblage reported here corresponds closely with those from middens in the Culbin Sands. The difference in species present in the these two deposits is likely due to the factors discussed by Coles and Taylor (ibid.). Notably absent from all deposits were fish bone, animal bone, and antler, apart from one very small bone fragment from context (5004), the deposit underlying D2.

The lower, Late Iron Age deposit provides additional evidence of Iron Age occupation of the area to that which has emerged at the Findhorn Dunes Site (beads, rotary quern fragment; Sharpe 2020). The upper, Early Medieval deposit is contemporary with the upper deposits at Sands of Forvie, Aberdeenshire, where shell fish harvesting was being carried out on an “industrial scale” (Noble et al. 2018), and which is a coastal sand dune complex very similar to that at Findhorn. It may also be contemporary with a probable Medieval farmstead at Cullerne as evidenced by Medieval rig and furrow visible in air photos (Greig 2001).

The post-excavation section shows that the midden continues eastwards into an area that may be relatively intact, and so in future there may be scope for further investigation. This might reveal, for example, that the shellfish were being cooked in pits using hot stones, as they evidently were at the Sands of Forvie (Noble et al. ibid).

Post excavation research design

Lithics analysis

The chipped pebbles recovered from the lower midden deposit might benefit from specialist analysis.

Perforated shells

The author has observed on the nearby foreshore that many cockle shells display similar perforations to those from the midden, and that this is likely the result of natural processes. No further analysis is being undertaken.

Bibliography

Black, G.F. (1891) ‘Report on the archaeological examination of the Culbin Sands, Elginshire,

obtained under the Victoria Jubilee Gift of His Excellency Dr R H Gunning, FSA Scot’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 25, pp. 498–511.

Callander, J.G. (1911) ‘Notice of the discovery of two vessels of clay on the Culbin Sands, the first containing wheat, and the second from a kitchen-midden, with a comparison of the Culbin Sands and the Glenluce Sands and of the relics found on them’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 45, pp. 58–81.

Chartered Institute for Archaeologists Standard for archaeological excavation. Available at: https://www.archaeologists.net/codes/cifa (Accessed: 07/01/2024).

Coles, J.M., Taylor, J.J. (1973) ‘The excavation of a midden in the Culbin Sands, Morayshire’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 102, pp. 87–100.

Greig, M. (2002) ”Aerial Reconnaissance, Moray [sites recorded while preparing a management plan for RAF Kinloss]”, Discovery and Excavation in Scotland, 3, pp. 80–81.

Kenward, H.K., Hall, A.R. and Jones, A.K.G. (1980) ‘A tested set of techniques for the extraction of plant and animal macrofossils from waterlogged archaeological deposits.’, Science and Archaeology, 22, pp. 3–15.

Moray Council Construct a meditation sanctuary at 46 The Park, Findhorn, Forres, Moray IV36 3TD Available at: https://publicaccess.moray.gov.uk/eplanning/simpleSearchResults.do?

action=firstPage (Accessed: 20/10/23).

Moray Historic Environment Record. Available at: https://online.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/smrpub/master/default.aspx?Authority=Moray (Accessed: 04 January 2024).

Natural Environment Research Council British Geological Survey [Geology Viewer]. Available at: https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/ (Accessed: 06/06/2024).

Noble, G., Turner, J., Hamilton, D., Hastie, L., Knecht, R., Stirling, L., Sveinbjarnarson, O., Upex, B. and Milek, K. (2018) ‘Early Medieval Shellfish Exploitation in Northwest Europe: Investigations at the Sands of Forvie Shell Middens, Eastern Scotland, and the Role of Coastal Resources in the First Millennium AD’, Journal of island and coastal archaeology, 13(4), pp. 582-605 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2017.1329242.

Scottish Government Scottish Remote Sensing Portal. Available at: https://remotesensingdata.gov.scot/data#/list

Scottish Government (a) CANMORE: National record of the historic environment. Available at: https://canmore.org.uk/

Sharpe, M. (2020) Findhorn Dunes Site, Evaluation, Discovery Exav Scot 20 p141.

Sharpe, M. (2021) Cullerne Midden, Excavation, Discovery Exav Scot 21 pp 91–92.

Shennan, I., Bradley, S.L. and Edwards, R. (2018) ‘Relative seal level changes and crustal movements in Britain and Ireland since the Last Glacial Maximum’, Quaternary Science Reviews, 188, pp. 143–159.

Struever, S. (1968) ‘Struever, Stuart. “Flotation Techniques for the Recovery of Small-Scale Archaeological Remains.”, American Antiquity, 33(3), pp. 353–362

Photographs

Illus 7: Pre excavation photo of midden (photo 08)

Illus 8: Post-clean, pre-excavation (photo 11).

Illus 9: Cleaned surface of D2, pre-ex., with some of D1 remaining in the section, above (photo 20)

Illus 10: Lens of shells within D1 (upper section), and below, surface of D2C (D2 upper levels in section)

(photo 27).

Illus 11: Sondage through the buried soil horizon (5004)

showing the pale natural below (5010). The upper (D1)

and lower (D2) midden deposits are visible in the section (photo 42).

Illus 12: (L–R) Small finds 401, 402, 403, from contexts 5005, 5004, 5001,

respectively (photo 51).

Illus 13: Clockwise from upper left: small finds 409, 405, 407, 410, 406, 404, 411. All from context 5004 (photo 52).

Illus 14: Perforated cockle shells from context 5005: small find No 412 (photo 53).

Illus 15: Charred wood and shell fragments from the upper deposit D1 (5001), (photo 59).

Illus 16 Cockle shell from lower midden deposit D2B (5006), during processing of samples (photo 54).

OASIS/DES Entry

Appendices

For appendices please see the pdf-flip book above.

I recently retired from 10 years in commercial archaeology, which followed an MLitt degree at the University of the Highlands and Islands in Orkney. I am also a photographer.

That is very interesting Michael, loved reading this! It’s exciting to imagine long gone eras this way. Thank you!