…Contrary to popular opinion, the Findhorn Community was not solely founded on beach sand and couch grass, Eileen Caddy’s inner guidance, Dorothy Maclean’s conversations with angels, and Peter Caddy’s heroic efforts with compost and cabbages. To Peter’s mind there was nothing accidental about its creation, although he kept this information to himself. All along, he had been inspired by and charged with the mission of creating something that would be a centre of demonstration and the proving ground for a spiritual tradition and set of moral principles that have been handed on to successive generations for centuries.

– Jeremy Slocombe, “Peter Caddy, the Rosicrucians and the Foundations of the Findhorn Community”

Introduction

As Jeremy Slocombe points out in his paper Peter Caddy, the Rosicrucians and the Foundations of the Findhorn Community, there was more to the beginnings of the Findhorn Community than Eileen’s guidance, Dorothy’s communication with the Devas, and Peter’s discoveries in the Garden. Peter Caddy was also informed by strands of the Ancient Wisdom – specifically the Western Mystery Tradition (also known as “Western Esotericism”) – leading back to classical times. In his article The Perennial Wisdom, Keith Armstrong discusses the roots and meaning of some of this knowledge. These threads – which included Alchemy, the Jewish system of Qabalah (and the later Christian Qabalah), Hermetic Magic and much more, and incorporated the passing of this knowledge via the advanced scientists, mathematicians and philosophers of the Arab world – were drawn together during the Renaissance by a number of thinkers in Europe.

However it was the publication of three documents by a mysterious “Rosicrucian Brotherhood” that brought these studies out into the open and provided a stimulus for the scientific and philosophical discoveries that exemplified the Enlightenment of the 18th Century. Whether or not this Brotherhood actually existed is a question in itself, but the three “manifestos” gave birth to actual organisations and informed Freemasonry and the magical orders of the late 19th Century. One such “Rosicrucian” organisation was the Roscrucian Order Crotona Fellowship (ROCF), of which Peter Caddy was a member in the 1930s. Founded on what could be described as traditional Rosicrucian principles, its lectures and teachings included an entire system for personal development that formed a fundamental part of Peter Caddy’s esoteric training and directed aspects of the Community’s development under his guidance including such techniques as the Laws of Manifestation which derived directly from this work. This article traces the history of Rosicrucian thought and tells the story of the Order to which Peter Caddy belonged, and its founder, Dr Sullivan.

A Source of the Mysteries

Nick Rose, writing on the Western Mystery Tradition, recalls that in the mid-1970s, Community co-founder Peter Caddy held regular talks on “The Foundations of Findhorn”, which covered a wide range of topics, from his travels in Tibet to UFOs. During these talks he would mention, almost in passing, that the Foundation was a Mystery School in the Pythagorean tradition. To grasp the meaning of that statement we have to go back in time, not only to Peter’s initial spiritual training, but much further back to the Renaissance and beyond, to the birth of Western esotericism – which is another name for the “Western Mystery Tradition” – in the Eastern Mediterranean, where Hermeticism, Gnosticism and Neoplatonism developed independently of mainstream Christianity.

Over time, these threads, along with the Qabalah, developed on parallel courses. The Qabalah was originally a set of mediaeval Jewish esoteric teachings that seeks to understand the nature of God and the universe. It originated in the late mediaeval period, with roots in earlier Jewish mystical traditions. In the 12th and 13th centuries, in Spain and to a lesser extent in France, Christian scholars developed a Christianised version of the Qabalah. Qabalistic magic, a form of magical practice that draws upon the teachings and symbolism of Qabalah, has been influential in Western occultism and is a key component of Hermetic Qabalah, a syncretic tradition that combines elements of various mystical traditions including both those noted above and alchemy, which was a system purportedly for transmuting base metals into gold (and as such led to the development of early chemistry), but with equal validity could be construed as a system of personal “spiritual transmutation” to a higher level of consciousness.

The Travels of Dr Dee

Dr John Dee: A 16th-century portrait by an unknown artist

A key figure in the bringing together of these disparate strands during the Renaissance was Dr John Dee. Dee (1527–1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and occultist known for his significant contributions to various fields of study during the Renaissance. Dee’s contributions to the occult and his involvement in mystical practices, influenced in some areas by the work of philosopher Paracelsus (c. 1493-1541), aka Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus, have made him a prominent figure in esoteric traditions. Dee, in common with several scholars and intellectuals during the period, travelled widely in Europe. In the late 1580s, Dee traveled to Poland, where he sought the patronage of King Stephen Báthory. He spent some time at the royal court in Krakow, and he visited several German cities during his travels, including Frankfurt and Bremen. The late 1580s and early 1590s found him in Bohemia, particularly in Prague, where he had audiences with the Emperor Rudolf II and engaged in alchemical studies.

The Rosicrucian Story

Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis (page 1)

1614 saw the publication of a document which, along with two others, caused excitement all over Europe. It was a manifesto, called the Fama Fraternitatis (The Fame of the Brotherhood), published in Kassel, Germany. This manifesto called for the restructuring of the sciences and religious practices and described the supposed life and travels of Christian Rosenkreuz, a mythical person living in the 14th and 15th centuries who supposedly traveled to the East in search of esoteric knowledge. It claimed that Rosenkreuz lived to be 106 and that his body was placed in a concealed tomb with perpetual lights, hidden for the following 120 years. It also invited interested parties to join a Brotherhood, which they could do simply by revealing their interest, which the Brotherhood would hear about and make contact. No-one, as far as we know, ever heard from the Brotherhood.

Two more manifestos followed the Fama: the Confessio Fraternitatis (The Confession of the Brotherhood), author unknown, and the Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosencreutz anno 1459 (published in 1616, Strasbourg, though it was probably written before the other two manifestos; in English, the “Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz in 1459”). These texts elaborated on the Rosicrucian ideals, emphasizing the blending of spirituality, science, and alchemy. The authors of these manifestos remained anonymous, contributing to the mystery surrounding the movement’s origins.

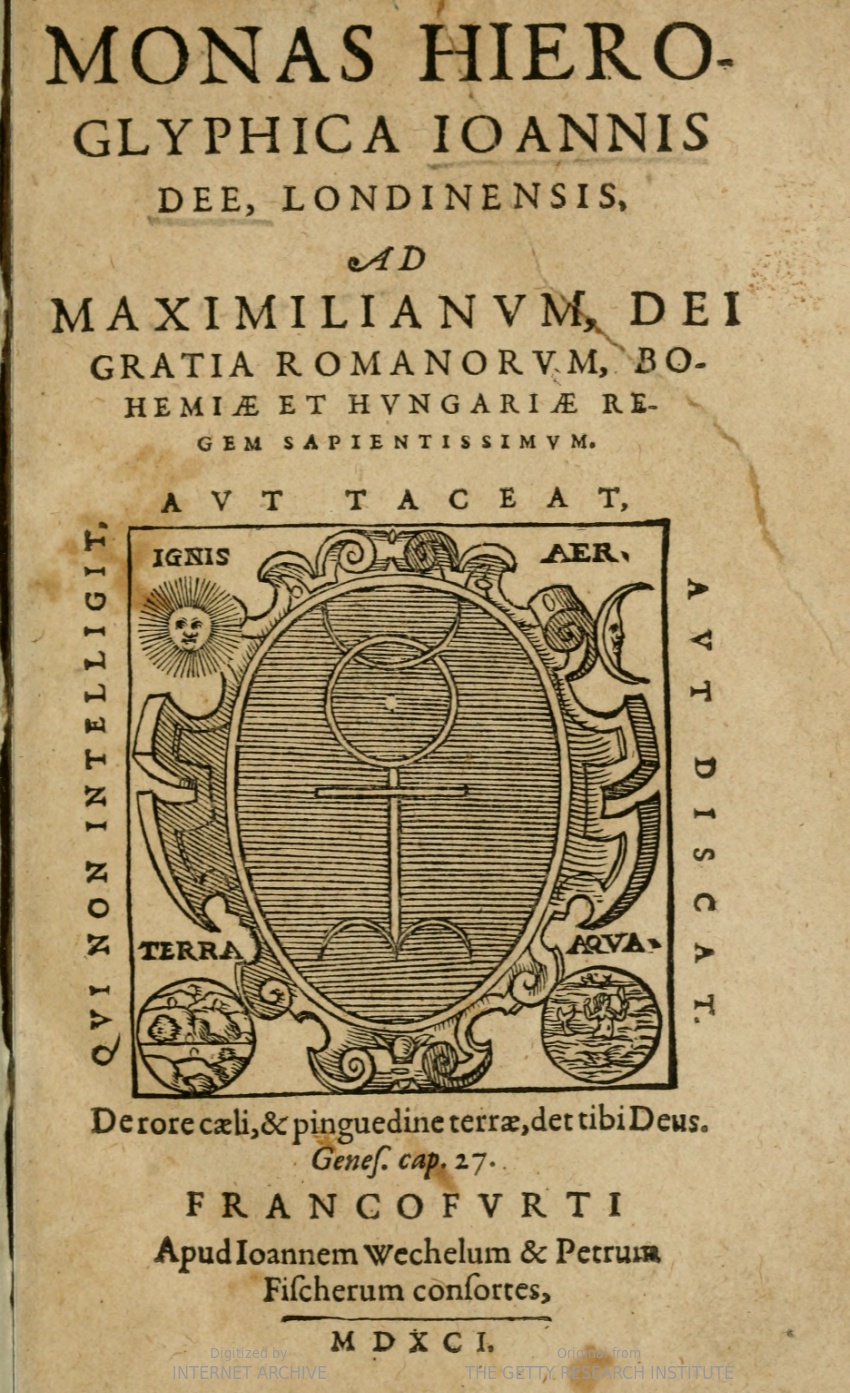

The cover of Dr Dee’s Hieroglyphic Monad (Internet Archive)

The “Chymical Wedding” is particularly interesting. It is an allegoric tale divided into Seven Days, or Seven Journeys, and recounts how Christian Rosenkreuz was invited to attend a wonderful castle full of miracles, in order to assist the [Al]Chymical Wedding of the king and the queen, ie, the husband and the bride, equivalent to Sun and Moon. The invitation to the royal wedding includes the symbol invented and described by John Dee in his 1564 book, the Monas Hieroglyphica. The “Hieroglyphic Monad” as we call it in English, described the meaning of this unique quasi-astrological symbol. Dee’s book was also bound with The “Confessio”, the second manifesto.

This combination of the two documents might not simply represent the pairing of two compatible works by the printers. Writing in the 1970s, Frances Yates (The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, 1979) suggested that the “Rosicrucian” philosophy itself was the result of the pulling together of the several previously-described historical and philosophical threads by Dr Dee himself. However, while rather appealing, this idea has been discredited in recent years.

A Potential Author

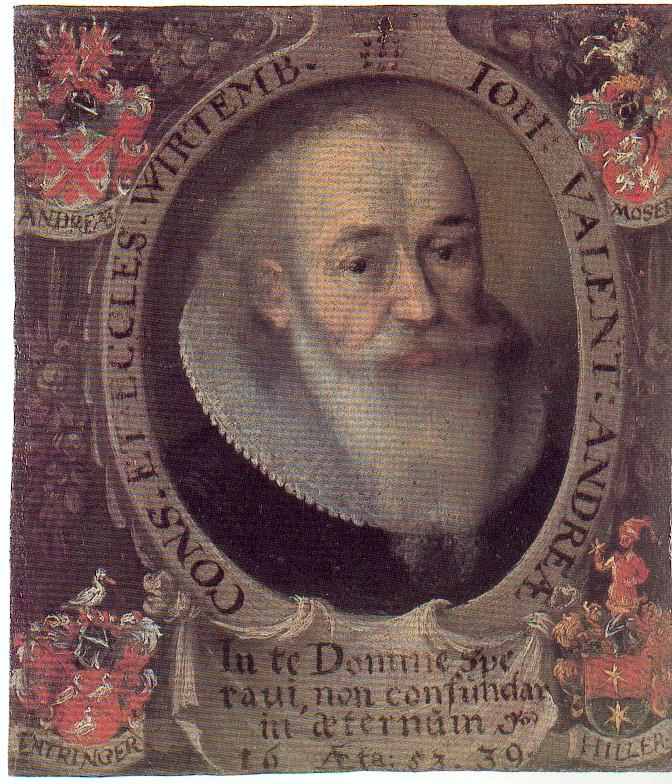

Johann Valentin Andreae (1586-1642)

Johannes Valentinus Andreä or Johann Valentin Andreae, a German theologian and Protestant utopianist, was allegedly the author of the “Chymical Wedding”, and it is suggested that he also wrote or co-wrote the Fama, although the Wedding’s character is markedly different. Some or all of the “Rosicrucian” documents may have been hoaxes, but their existence led to the foundations of Rosicrucianism, a movement which had a significant impact on the development of the sciences in the following Age of Enlightenment.

On Andreae, Wikipedia notes: “Andreae was a prominent member of the Protestant utopian movement which began in Germany and spread across northern Europe and into Britain under the mentorship of Samuel Hartlib and John Amos Comenius. The focus of this movement was the need for education and the encouragement of sciences as the key to national prosperity. But like many vaguely-religious Renaissance movements at this time, the scientific ideas being promoted were often tinged with hermeticism, occultism and neo-Platonic concepts. The threats of heresy charges posed by rigid religious authorities (both Protestant and Catholic) and a scholastic intellectual climate often forced these activists to hide behind fictional secret societies and write anonymously in support of their ideas, while claiming access to “secret ancient wisdom”.”

One of the concepts embodied in the Manifestos was that of the “Invisible College”, noted by Ben Jonson. The term “The Invisible College” was used for a small group of scholars who met together on a regular basis in 1646-7. It’s suggested that this group, which may have included Christopher Wren and scientist Robert Boyle, was, alongside the Gresham College Group, a precursor of the Royal Society, but this is hard to establish. An early member of the Royal Society was Elias Ashmole, founder of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. He was also an early Freemason, and interested in the Rosicrucian material.

A Lasting Influence

The Rosicrucian manifestos generated a flurry of interest and debate throughout Europe, with various writers opposing or defending the Rosicrucian documents. In England, a notable defender was the scientist and philosopher Robert Fludd (1574-1637) in his Apologia Compendiaria. Various individuals were inspired to seek esoteric knowledge, and the movement became closely associated with the promotion of scientific and spiritual enlightenment. The ideas promoted by the Rosicrucian Manifestos, and those promoting them, had a lasting influence on the Age of Enlightenment, particularly in the fields of alchemy, science and natural philosophy, and Freemasonry. Many intellectuals and alchemists were drawn to the Rosicrucian ideals, using them as a source of inspiration, even though the historical authenticity of Christian Rosenkreuz and the events described in the manifestos remained (and remain) subjects of debate. Indeed, some scholars view them as symbolic or allegorical works rather than factual accounts.

The Rose Cross

Nevertheless, the Rosicrucian movement has left a lasting mark on Western esotericism. While the early Rosicrucian manifestos may have been more allegorical than factual, they laid the foundation for various organizations that emerged in the centuries that followed. These organizations often claimed to be heirs to the original Rosicrucian tradition. For example, there has long been a “Rosicrucian” strand to the higher orders of Freemasonry, exemplified by the Societas Rosicruciana (Rosicrucian Society), a Rosicrucian order with branches in several countries, which limits its membership to Christian Master Masons. The Societas Rosicruciana claims a link to the alleged original Rosicrucian Brotherhood, via the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross (Orden des Gold- und Rosenkreutz, aka the Fraternity of the Golden and Rosy Cross), a German Rosicrucian organization founded in the 1750s by Freemason and alchemist Hermann Fictuld, which bases its teachings on those found in the original Rosicrucian manifestos along with other similar publications from the period.

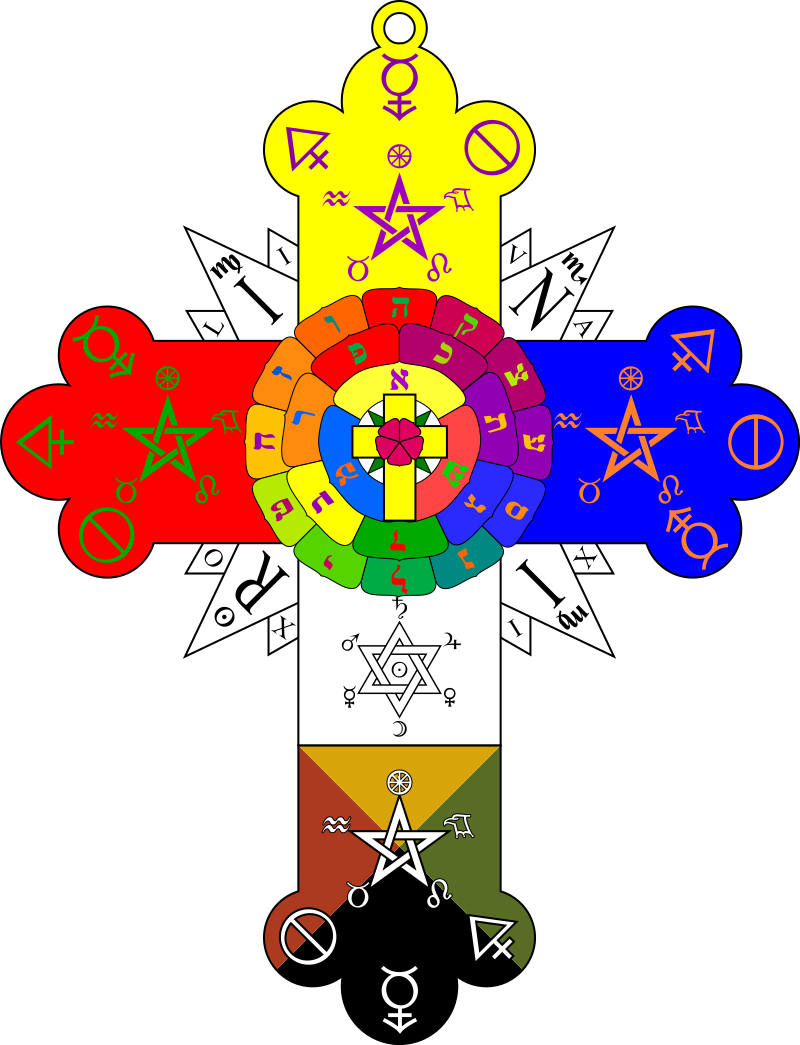

Rose Cross Lamen, Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

Organisations claiming Rosicrucian origins and philosophy appeared during the 18th and in particularly the 19th centuries. Particularly notable was the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which was a magical Order founded partially by members of the Societas Rosicruciana In Anglia (SRIA), whose symbol was an elaborate version of the Rose Cross and whose degree structure derived from that of the SRIA which drew in turn from the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross. Other organisations appeared in Britain and in North America.

One could say that although it is unlikely that the “original” Rosicrucian Brotherhood actually existed, the interest surrounding and subsequent to the publication of the original documents inspired the development of real institutions and organisations dedicated to the advancement of knowledge – some of which laid the groundwork for advances in scientific and other research during the subsequent centuries.

The Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship

Cover of a Rosicrucian pamphlet published by ROCF

George Alexander Sullivan (1890-1942) was born in Liverpool, Lancashire, on the 24th of September, 1890, son of Charles Washington Sullivan and Catherine Condon. At the age of 21, he received instructions from someone he refers to as “my ancestor J.S.” (who this might be is not apparently known, though the “S” quite possibly refers to an earlier, unknown Sullivan) to found “an Occult Society in which the Rosicrucian Teachings might be taught to those willing to undertake such studies.” The Society he founded was called the Order of the Twelve, and remained in existence until it was disbanded at the outbreak of the First World War. Following the War, in 1920, Sullivan reconstituted the organisation under the name “Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship” (ROCF), of which he was Supreme Magus. Steven J. Sutcliffe, writing in Children of the New Age: A History of Spiritual Practices (p. 43) notes that the ROCF was “rejuvenated by Rosicrucian lore Sullivan claimed to have learnt in Germany during a period in captivity”. An alternative genealogy is given in another pamphlet, where the ROCF is said to have existed in its present form for ‘at least one hundred years’ and even to be descended from the ‘Antient [sic] Rosicrucian Adepts of 1347’”. The ROCF was active at least until around Sullivan’s death in 1942. Crotona was the town in Italy where classical mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras had his Mystery School in the 6th Century BCE: a potent link between his Order and the Western Mystery Tradition. In a number of documents, Sullivan is named as “Dr Sullivan”, but his doctorate is unspecified.

Sullivan was a prolific writer and by the mid-1920s the Order had published over 130 pamphlets and periodicals on esoteric matters under the “Bohemian Press” or “Crotona Press” imprints (digitised versions of many of these publications can be found in the Southampton University Digital Library,Rosicrucian Collection, Special Collections, Hartley Library or the Internet Archive), the majority penned by Sullivan, whose esoteric name was “Aureolis” – possibly inspired by “Aureolus”, one of the names of Renaissance alchemist and philosopher Paracelsus. The logo of the ROCF was a rose-wreathed cross set against a radiant five-pointed star (see pamphlet cover illustrated). The Order met in Liverpool and also at a location in London, until 1935, when the Order relocated to Somerford near Christchurch in Hampshire.

A Course in Mysteries

Pamphlet issued under the name of the Liverpool College of Psychotherapy

The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals notes that in 1920, Sullivan had run the Liverpool School of Mental Science, which the ROCF ran in the late 1920s as the Liverpool College of Psychotherapy & Natural Therapeutics. He also produced a periodical, The Rosicrucian Gazette and later (from mid-1935) The Uplifting Veil. The latter claimed to be the product of an “Academia Rosae Crucis” offering teaching in seven areas: Masonic (Symbology), Ordo (Occult Science, Mental Science, etc.), Temple (Comparative Religion, Mysticism, Latin), B.O.H. (Therapeutics, Healing, Magic, College of Psychotherapy (Practical subjects for outside work)), The Drama (Elocution, Plays, Oratory, The Arts), the School of Adepts (2nd degree, 2nd Point and onwards). It included articles by Aureolis, C.E. [Catherine Emily] Chalk, Raj Bahai and others.

The first edition of the periodical publication, “The Uplifting Veil”

J C Ruthven, writing for the University of Southampton Special Collections, provides a slightly different account of the teachings that the ROCF offered. “For members of the group, Sullivan provided instruction through the Academia Rosae Crucis. Its programme took the form of three degrees, Licenciate, Bachelor and Doctor, the subjects studied being: Principles of Rosicrucian Philosophy and History, Mythology and Symbology, Comparative Religion, Oratory and Drama, Alchemy, Therapeutics, Psychology, Mysticism, Occult Science and Principles of Magic. Teaching took the form of lectures and discussions as well as rites and ceremonies which were held in the Ashrama Hall [in the Christchurch location], adjacent to the theatre. For those who could attend neither the Christchurch nor the London ‘chapters’, instruction was also offered by correspondence course.”

Meanwhile, in 1912, a Rosicrucian order called the Order of the Temple of the Rose Cross had been founded by Annie Besant,(1847–1933) a leading British social reformer, women’s rights activist and Theosophist – at one point she was President of the Theosophical Society. It was a development of her involvement in Co-Masonry (aka Co-Freemasonry, a version of Freemasonry that admits women, where traditional Freemasonry does not). The Order however only lasted until 1918. Annie Besant’s daughter, Mabel Besant-Scott (1870-1952) picked up the reins of Co-Masonry after her mother’s death, and briefly became the head of the British Federation of Co-Freemasonry, but she resigned in 1934 to join the ROCF, taking with her some of her followers in Co-Masonry, becoming active members of the ROCF during its time in Christchurch. And according to Sutcliffe, “A significant minority among students of Alice Bailey’s Arcane School were members of the Crotona Fellowship.”

The Order in Christchurch

Additional information on the development of ROCF comes from several sources, noted in the Wikipedia page describing the Order:

“In 1930, a group of members of the order local to the Christchurch area began to meet regularly at a pub [possibly the King’s Arms Hotel] in Christchurch, and at about the same time the annual ‘conclave’ was held in nearby Bournemouth. Some time later the group decided that a more permanent venue was required. (See Philip Heselton, Wiccan Roots: Gerald Gardner and the Modern Witchcraft Revival)

A book of some of the plays written by Sullivan under his writing name, Alex Mathews, for performance at the Garden Theatre

“The group’s headquarters near Christchurch was a wooden building named the Ashrama Hall, completed in 1936 in the garden of a house owned by Catherine Chalk, who probably also started the original meetings in the pub. In 1938, on the same land, the group built the Christchurch Garden Theatre, referred to as ‘The First Rosicrucian Theatre in England’. From June–September 1938 it presented mystically themed plays, written by Sullivan under his journalistic pen-name Alex Mathews.”

“Sabina Magliocco, in her examination of the influences of the study of folklore on the development of Wicca (Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America), considers it possible that by the late 1930s some members of the Crotona Fellowship were performing Wicca-like rituals based on Co-Masonry, and that this was the group referred to by Gerald Gardner (1884-1964, the founder of modern Wicca) as the ‘New Forest Coven’.”

The Wikipedia page goes on, “The numbers attending Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship events always were small, and the group is best known today for its association with Gerald Gardner and Peter Caddy. Following the death of George Alexander Sullivan in 1942 (which he apparently predicted), the group’s activities and membership diminished. By the early 1950s their focus had moved to Southampton. Correspondence between former members suggests the Order ‘existed in memory only’ by the early 1970s.”

An organisation called “Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship” apparently exists today, with a US-registered website at crotonafellowship.com and a more Wiccan focus than appears to have been the case in the original Order. Its “About” page gives an account of the history of the Order from their point of view which is broadly in line with the account given here, while providing some additional information (probably sourced from Sutcliffe):

“The Grand Chapter of the Crotona Fellowship first operated in Birkenhead (c. 1924) and Liverpool (c. 1927) before moving to Christchurch in late 1935 and entering its most productive period… thirty-six members — barristers, solicitors, small business operators, teachers, and clerical workers — attended its annual gathering in 1937.”

It was into this organisation that Peter Caddy came in 1936 on the invitation of his brother in law (wife Nora’s brother) Jim Barnes, and the story of Peter’s participation in the Order and its activities from 1936 to 1947 (ie until Peter was obliged to leave after the split with Nora) is discussed in Jeremy Slocombe’s paper. It is interesting to speculate whether or not Peter knew Gerald Gardner, who was involved in the ROCF (we don’t know for certain whether as a full member or as an associate of some kind) from 1938 to 1940. It seems rather likely.

Peter Caddy could not always attend meetings in London or Christchurch (indeed, several of the Order’s practices were structured for solo rather than group work, so this may have been common), so it was as a part of the correspondence course mentioned earlier that he was sent the “Soul Science” lectures and also learned the power of Affirmation, knowledge from which he brought to bear in the development of the Findhorn Community. Alongside instructive tales from his past, they became the inspiration for the “Foundations of Findhorn” presentations that Peter gave to the Community in the mid-70s.

Sullivan’s Rosicrucian Heritage

The British Rosicrucian scene of the late 19th/early 20th Centuries seems to consist mainly of Masonic groups like the SRIA, and although from the ROCF documents we can indeed discern a Masonic influence including a somewhat unusual degree structure with “Points” as well as Degrees, there is also a strong strand of personal development and the power of positive thinking in the materials – as evidenced by the “Soul Science” lectures – which might be regarded in part as the foundations of the “Laws of Manifestation” – and this leads one to wonder where Sullivan found his Rosicrucianism. It was quite possibly not from the hallowed lodges of the SRIA or its sister organisations, which appear to have a rather different degree structure. We have already noted that it has not been possible to identify Sullivan’s “ancestor J. S.” who was responsible for passing the secrets on to him. It seems to be worth considering whether the inspiration for the ROCF came not from Britain, but from the United States, where the plethora of “Rosicrucian” groups all seem to include a strong current of personal development while at the same time claiming some kind of historical descent from European roots (and we note that Sullivan claims his organisation’s roots extended back 100 years, and even to the “Antient Rosicrucian Adepts of 1347”).

Three American organisations are of special interest in this context. One is H Spencer Lewis’s Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC), today the most widespread “Rosicrucian” organisation in the USA, and which is notable for explicitly not having a connection with ROCF – this is specifically stated in several places, notably in Jeremy Slocombe’s paper.

Another is the Fraternitas Rosae Crucis, which traces its ancestry back to P. B. Randolph, but whose primary formative character was R. Swinburne Clymer, Lewis’s nemesis. At a cursory glance, there seem to be no specific factors that might point to the FRC as an inspiration for ROCF.

Rosicrucian Fellowship emblem (after Max Heindel, modified by Gabriel Falcon, public domain)

Front page, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, Max Heindel, 1909

Another possible candidate is Max Heindel’s Rosicrucian Fellowship. Heindel (1865-1919) was the author of a weighty tome, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception (1909) and other works. We can note first of all a passing resemblance between the names of the two organisations. In addition, if we take a look at the logos of the two organisations, we note that they are somewhat similar – a rose-wreathed cross before a brilliant five-pointed star (see the illustration shown here and on the pamphlet cover above). However, the Fellowship has a tendency towards a religious character (“Mystic Christianity”) which probably would not have inspired Sullivan or his ancestor – although curiously their “New Thought” style might have appealed to Eileen! However, there appears to be no explicit evidence for Heindel’s organisation being any kind of source for Sullivan and the ROCF.

It would seem, then, that there is only circumstantial evidence for locating the origin of the Rosicrucian features of the ROCF – this is currently a bit of a dead end. As Sutcliffe puts it, “The ROCF is best located within the hybrid, quasi-Masonic currents of late nineteenth-/early twentieth-century ‘vernacular’ Rosicrucianism.”

I first visited the Community for Experience Week in August 1976 and thereafter returned on numerous occasions to attend and/or help at workshops, conferences and related events. I moved to the area in 2017.

Leave A Comment